The Bicycle and the Ride to Modern America

Susan B. Anthony said, "cycling did more to emancipate women than anything else in the world."

On May 10, 1884, midway through his 48th year, Samuel L. Clemens reluctantly “confessed to age” by wearing glasses for the first time. That same day, the celebrated writer better known as Mark Twain sought to reclaim his youth by mounting a bicycle for the first time.

Only one of these first tries succeeded. “The spectacles,” Twain later recalled, “stayed on.”

Bodily contusions notwithstanding, Twain promoted the new sport of cycling with characteristic rhubarb tartness. “Get a bicycle,” he urged readers. “You will not regret it, if you live.”

Over the next decade, millions of Americans of all ages, trades and visual acuities would heed the pedaler’s cry. They would not only live, but would learn to stay majestically, propulsively upright, too. They would start cycling clubs, collect cycling paraphernalia, compose cycling songs, silk-screen cycling art, overhaul female fashion and rewrite the rules of social conduct.

The end-of-the-century bicycle craze also greased the gears of industrial genius, as manufacturers here and abroad scrambled to devise new ways to speed up and standardize production, to lighten the bicycle frame without compromising its strength, and to make the ride cushier through the addition of a radical new invention, the pneumatic tire.

The full-bore bicycle fever was brief, and by the early 20th century it had given way to fascination with the automobile. Yet, as a new exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History makes clear, the impact of the bicycle on the nation’s industrial, cultural, emotional and even moral landscape has been deep and long lasting.

In addition to air-filled rubber tires, we can thank the bicycle for essential technologies like ball bearings, originally devised to reduce friction in the bicycle’s axle and steering column; for wire spokes and wire spinning generally; for differential gears that allow connected wheels to spin at different speeds.

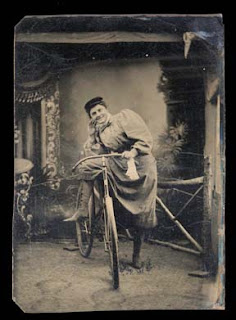

An 1890s portrait showing a bicycle not all that different from what is being ridden today.

And where would our airplanes, tent poles and lawn furniture be without the metal tubing developed to serve as the bicycle frame? “The hollow steel tube is a great form,” said Jim Papadopoulos, an assistant teaching professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern University in Boston. “It’s tremendously structurally efficient, light and strong, and it came into being for the bicycle.”

Bicycles also gave birth to our national highway system, as cyclists outside major cities grew weary of rutted mud paths and began lobbying for the construction of paved roads. The car connection goes further still: Many of the bicycle repair shops that sprang up to service the wheeling masses were later converted to automobile filling stations, and a number of pioneers in the auto industry, including Henry Ford and Charles Duryea, started out as bicycle mechanics. So, too, did the Wright brothers.

"Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving."

-- Albert Einstein

“The pre-story is so important,” said Eric S. Hintz, a historian with the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. “You don’t get automobiles unless you first have bikes.”

David Hounshell, the author of “From the American System to Mass Production: 1800-1932,” described the bicycle as “one of the classic artifacts of industrial civilization,” adding that “it still prevails, and there are billions of them around the world. It’s a universal technology.”

The bicycle has pride of place at the Smithsonian as part of a larger interactive exhibit called Object Project, which features everyday objects that we often take for granted, including refrigerators, ready-made clothing and home heating systems.

The Depression-era refrigerator on display looks like a kitschy Hollywood prop, and the hulking proto-bike called the high wheeler — with its 60-inch front wheel and little cellular bud of a rear balancing wheel — looks strictly Barnum & Bailey. Intriguingly, though, an early “safety bike” of the collection, from 1896, looks almost contemporary and fit for a spin.

Its wheels are of equal, hip-high size and girdled in natty white rubber, and its pedals are attached at the bottom of the seat column to a toothed crank that turns a chain that turns the rear wheel, while the steering column rises up from the axle of the front wheel — all just as they are on today’s bicycles.

The evolution of the bicycle was long, complex and multinational, and spattered with squabbles over provenance and patent rights.

Early versions like the high wheeler, in which the pedals were attached directly to the large front wheel, were clumsy, heavy, difficult to ride, easy to topple and expensive. Few beyond rich young men made a sport of them.

But with the advent of the crank, sprocket and chain system, small rotational movements of the pedals could be translated into large rotations of the rear wheel, and in the late 1880s, the safety bicycle was born — safer than the shake-and-break high rollers, that is, and possibly one of the most perfect machines the world has ever known.

A woman's bicycle in 1896. By the mid-1890s, some 300 American companies were churning out well over a million bikes a year. Credit National Museum of American History.

“I have a deep question about the bicycle,” said Andy Ruina, a professor of mechanical engineering at Cornell University who studies bicycle dynamics. “Was the bicycle invented or discovered? It’s such a pure concept, it seems like it existed in the universe even before people thought of it, like the wheel itself, or a prime number.”

The bicycle certainly is among the purest means of transportation. It’s roughly 50 times more energy-efficient than driving and four times more efficient than walking.

If you push one on level ground at a fast enough clip, it will just keep going, balancing itself en route just as a bike rider does. When it starts to fall to the left, it automatically steers to the left; when it leans right, it self-corrects by turning right.

Learning to ride a bicycle, then, may be less a matter of taking charge than of letting go, of suppressing the impulse to overcorrect the bicycle’s inherently stable momentum.

By the mid-1890s, some 300 American companies were churning out well over a million bicycles a year, making the safety bike one of the first mass-produced items in history. Among the most exuberant customers were women, who discovered in the bicycle a sense of freedom they had rarely experienced before.

The bicycle helped change fashions and social conduct, while paving the way for the airplane and the automobile. Credit National Museum of American History

Bicycles also seem to have minds of their own. Though often mistakenly considered inherently unstable, bikes can balance themselves. “It’s called ghost riding,” Dr. Ruina said. “We don’t really understand why, but all bicycles are close to stable.”

Comments

Post a Comment